Communication. That’s what email is all about. The same is true whether you’re using it to apply for a job, or to seek help from customer services… or to market your product to thousands of customers.

Marketing emails typically go to lots of different people using lots of different devices. Your objective is to convey an equally intelligible message to all of them. That brings us to the concept of accessibility.

Defining email accessibility

Firstly, here’s what accessibility is not:

- An inconvenience

- An afterthought

- Exclusively a matter of visual impairment

And now for what it is. Mozilla (the developers behind the Firefox web browser) describe accessibility as: the practice of making your websites usable by as many people as possible.

Applying this thinking to our favourite medium, it means emails that can be easily understood, navigated and interacted with. We want our mailings to render optimally in any application on any gadget. They must impart a clear message and invite a defined action from the customer. And accessibile emails are open to people whatever their level of physical ability.

Email accessibility is a huge topic, encompassing many human and technical factors. Let’s take a look at some of them.

Clarity in message, design and function

A marketing email usually performs two main functions:

- Communicates a message to your customers.

- Invites them to take action in response.

Concise copy and a user-friendly structure support those objectives. Worry not – that doesn’t mean your email needs to be sterile and unimaginative. There’s still plenty of scope for characterful writing and vibrant imagery. The art is in creating an eye-catching design that supports your message rather than overwhelming or obscuring it.

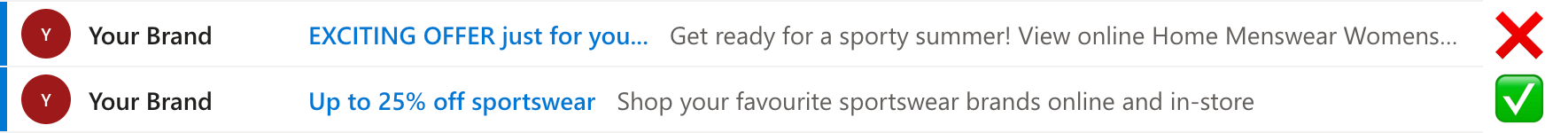

Accessible copywriting begins with the subject line. Good, honest information beats vague open-bait every time.

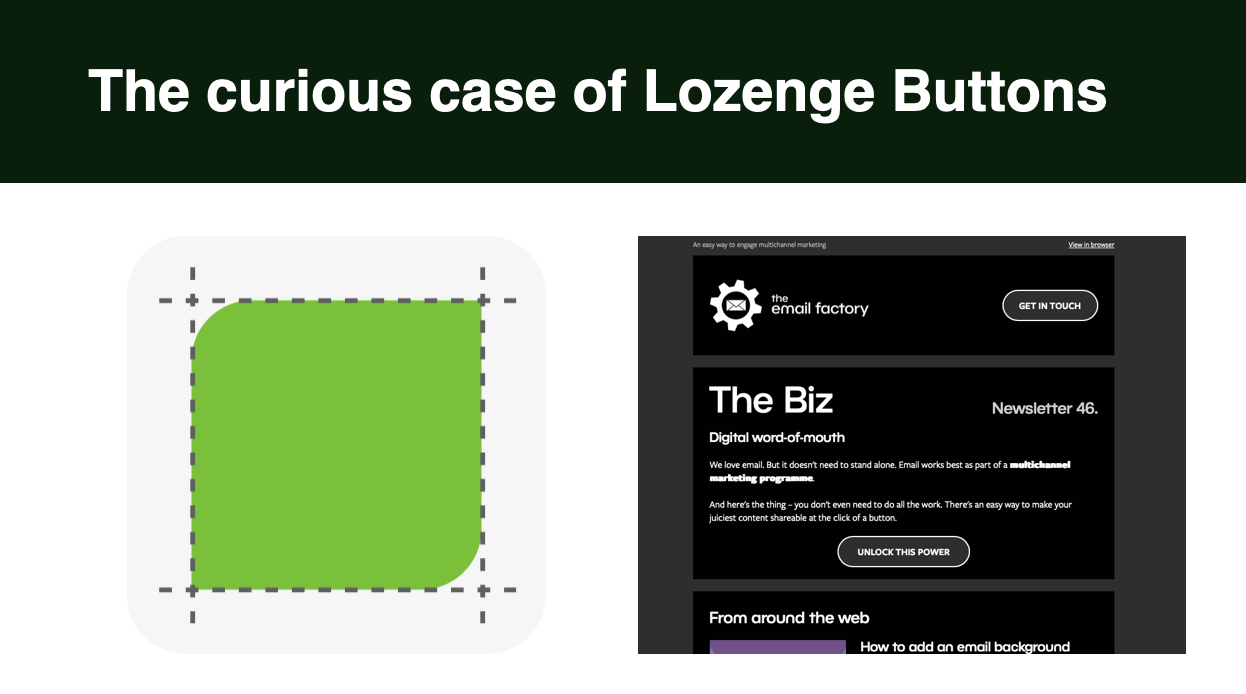

I like big buttons and I cannot lie

There’s a tendency in email marketing to go link-crazy. Every heading, every subheading, every image, every block of text… and even empty space – all clicking through to web pages. That usually means ambiguous destinations and multiple links to the same places. The technical term for this is a mess.

The solution: buttons. Big ones. Big ones with clearly defined calls-to-action. Your customer should know in advance what sort of content to expect upon pressing it. And don’t forget to include plenty of breathing space around those buttons. You don’t want links to different places squashed up against each other, especially on touch-screen devices.

Don’t get left in the dark

Dark mode took off a few years ago, and remains a popular display option among those who care about things like battery life and corneas.

It can have a dramatic effect on the way your email is rendered. And often not in a good way. Images can be camouflaged against recoloured backgrounds, or left floating in unsightly squares.

Email being email, the rendering methods for dark mode are not consistent from one email application to another. It therefore requires an assortment of coding and imagery techniques to create dark mode-friendly mailings. Dark mode-specific CSS classes are possible. PNG format images with border effects help them stand out, should they be unexpectedly displayed atop a dark background.

The technical details are a complex topic for another day. But let’s be clear on the objective – you want to optimise your email for dark mode, not override your user’s preferences.

So many apps, so many devices

Sorry in advance, but I’m about to throw a bunch of words at you. Here goes.

Desktop computers, laptops, tablets, mobiles. Screen sizes, model versions, display settings. Desktop software, webmail services, mobile apps.

My point: there are many software and hardware combinations out there, and your marketing emails could be viewed on any one of them. You want your email to be just as legible on a dusty old laptop running Microsoft Outlook 2016 as it is on a brand-new iPhone.

Responsive email – i.e. that which is coded to fit to any screen size – is the answer. It’s standard practice nowadays, but that absolutely does not mean that it is always handled adequately. All too often, mobile rendering remains a secondary concern – leading to visual problems like tiny text and confusingly mismatched imagery. We’ve written extensively about responsive email in the past, but let’s sum up some of the most important points:

- Plan your responsive design from the outset. The mobile layout should never be a secondary consideration.

- Support for HTML and CSS in email is extremely varied and somewhat limited. An email developer must understand how to code effectively for all major devices and email services.

- Be prepared to simplify an overly-ambitious design. Fanciness for the sake of fanciness is not in the spirit of accessibility.

Even if you’re confident that your email is perfection itself, always include a link for it to be viewed in a web browser.

Hear me out: your emails could be confusing to screen readers

I mentioned earlier that accessibility is not all about visual impairment. It is however an extremely important aspect, and will largely be the focus of the remainder of this article.

A screen reader is a piece of assistive software that will audibly describe the content of an application, web page… or indeed an email. You probably have a screen reader right in front of you right now. Press COMMAND + F5 if you’re on a Mac, or CTRL + WIN + ENTER if you’re on a Windows PC. While the use of a screen reader takes time to master, this will give you a helpful insight into how a visually impaired person might be interacting with your content.

As technically incredible as screen readers are, it is unfair to expect them to do all the work. A website must be designed and coded in a way that a screen reader can navigate and interpret. The W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) publishes extensive guideance on this topic, and a lot of the advice carries over to email.

Let’s take a look at some ways to develop emails with screen readers in mind.

Write semantic code

Do you shop in supermarkets? They have signage to help you find your way around the array of aisles. ‘EGGS’ here, ‘HOUSEHOLD ESSENTIALS’ over there. If those signs didn’t exist, your shopping experience would be a lot more frustrating. An email without semantic code is a bit like a supermarket without signs.

Semantic email code can be defined as meaningful HTML tags. These are the basic elements behind the scenes that make up a mailing. Here are a few important ones:

<header><nav><section><article><h1> (the main heading on the page)<h2> to <h6> (increasingly minor headings – seriously, I don’t think I’ve ever gone past h3)<p> (a paragraph)<strong> (bold text)<em> (italic text)<footer>

But there are also multi-purpose, non-descriptive HTML elements:

<div><span><table> (for the presentational purposes of email, that is)

Those last three are far from invalid. But it’s easy to be lazy in web and email development alike, and rely on them too heavily. In fact it’s actually somewhat rare to code particularly semantically in email.

But guess what – descriptive HTML tags help screen readers know what’s what. Say your main heading is just sitting there in a generic <span> tag. A screen reader won’t know that it’s any more significant than any other text that happens to be floating about on the page. If it’s wrapped instead in an <h1> tag, the screen reader will announce it as “heading level 1”. Now the user better understands what is being communicated. Construct your entire email with semantic code and you communicate useful information to those who can’t see it.

Similarly, sequence is important. Screen reader users will often be using a keyboard to navigate through the email. By default this will jump from item to item in the order they appear in your code. Make sure it makes sense.

And while there is actually a way to override this sequence, doing so is so far removed from best practice that we will discuss it no further! Far better to construct an email that follows a logical sequence in content and structure.

Mark your bricks as bricks

Modern websites are constructed with the finest materials available – divs, spans and all sorts of CSS-styled goodness.

Emails are built using a more… rustic method. They use HTML tables for structure, just as web pages did once upon a time.

When a screen reader encounters a table, it assumes that it is a table of data. Something like this:

A screen reader may therefore produce confusing results when dealing with the structural table of an email. There’s an easy fix for this. Just apply the following HTML attribute to all of the tables that comprise your email:

role="presentation"

Congrats – you’ve just told screen readers what your tables are for, and made your email immediately more accessible.

Let text be text

When you write a text message to a friend, do you take a screenshot of it and then send it as an image? Unless you’re charmingly eccentric, I suspect the answer is no.

The same principle applies to email. And yet countless companies – sometimes even the biggest of corporations – produce marketing emails in this roundabout manner. Paragraphs of text are drawn up in a design application, saved as JPEGs and dumped into HTML emails. Why?

This practice is so widespread that phrases such as ‘live text’ have sprung up. Let’s get out of that way of thinking. It’s just text.

There are probably multiple factors at play here. Brand guidelines and typography. A desire to achieve complex layouts in a medium that doesn’t make it easy. Or it could be the it’s-always-been-done-this-way mentality.

Accessibility and usability trump all of those things. There are all sorts of reasons to use proper text. It renders sharply and at a consistent size, whereas images shrink and grow. Users can zoom in without the letters becoming blurred. Chunks of text can be selected and copied. And it’s the purest form of copy for screen readers to detect.

Web fonts are reasonably well supported in email these days, so you don’t even need to lose your brand typeface. Now all of the boxes are ticked.

Pictures speak a thousand words

But only if you let them. And you should probably cut that down to a handful of helpful, descriptive words.

HTML comes equipped with a thing called alt tags. That’s short for alternative. These tags allow you to attach text content to any image on the page. We can use them to describe what is pictured or relay copy from a heading. Normally the alt tag goes unseen.

They are however of critical importance for users who cannot see your image. That might be someone who has chosen to turn pictures off, or perhaps the file has failed to load, or it could be a person with a visual impairment.

Take a look at a few examples:

alt="Overhead aerial photograph of a hotel's outdoor pool, surrounded by trees and rooftops"

alt="Watercolor painting of a pink flower on a plain background"

alt="SALE NOW ON"

Without these descriptions, the content of these images would be completely concealed to a screen reader user. By typing just a few words, you have produced an immeasurably more inclusive email.

One more thing – emails often include some purely decorative or spacer images. Just leave the attribute as alt="", and screen readers will know to ignore them.

Self access-ment

We’ve covered a reasonable amount here, but this is a topic too broad to fully explore in a single article. There are plentiful accessibility resources online, even for the relatively niche branch that is email.

Among those are tools to analyse the accessibility of your web page or email. Some of these are commercial products, but there are also some handy free ones.

Paste in your email code at accessible-email.org and you’ll see an instant report with suggestions for improving accessibility.

You might also wish to try WAVE – web accessibility evaluation tool. As the name states, this is intended for web pages. But much of the feedback also applies to email, so there’s nothing to stop you popping a ‘view online’ link in there.

Perhaps most useful of all is a simple checklist. That’ll let you score your emails consistently according to your particular requirements.

Here’s to more inclusive emails

Making your emails accessible is a complex task – but it doesn’t need to be an extra one. Accessibility standards are intertwined with email best practice. By putting accessibility at the core of your design and development process, you automatically produce better emails all round. Everybody benefits.

Perhaps the key to accessibility isn’t to think of it as a separate subject at all, but simply the act of making a good email.

![It’s just a [colour] theory](https://www.theemailfactory.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/blog-6.png)